He authored the book My Prison Walls, which details his experiences in captivity.

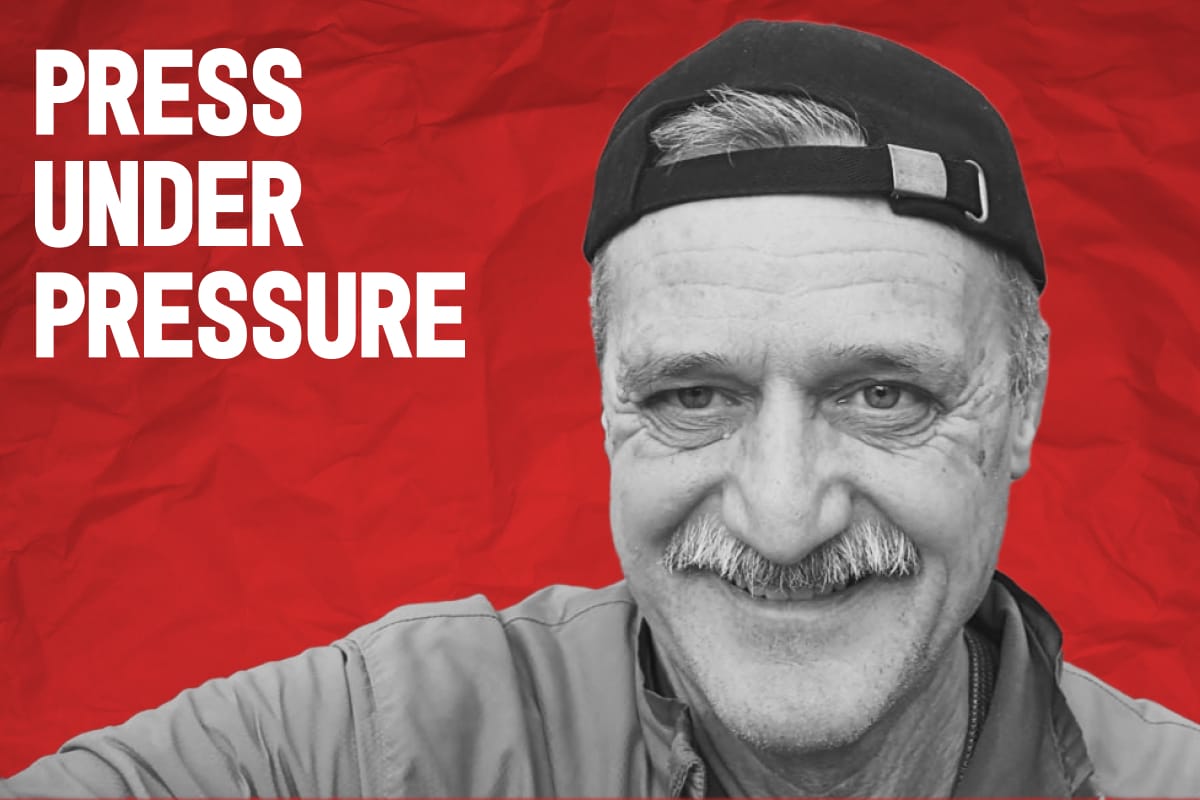

In this exclusive interview for the Press under Pressure project, the journalist discusses what it’s like being recognised by people in prison and in Vilnius. He also shares his experiences of detention, the conditions in prison and his current mood.

When I was a student I used to climb and we had cling holds, things you grab with your hand and pull yourself up. While in prison, I tried to establish such holds. My journalistic experience was part of it, of course. It was one of the cling holds.

When I went into the cell in the Minsk remand centre, I greeted the inmates in the usual way and told them I was just an ordinary guy. I saw an acquaintance and we recognised each other straight away, which made things easier for me. It’s good to be with someone you know, plus he’s been in that cell for a long time. He had authority, which helped me as well.

And that’s how it stayed – I was recognised everywhere. In that cell in the Minsk remand centre, there was also a man who did not recognise me by sight, but when he heard my name he said he remembered me as a journalist who worked for the newspaper Znamya Yunosti. In the 90s it was the most democratic newspaper. It was like TUT.BY at that time. And this man said: “It is such an honour for me, I will tell everyone how I shared a cell with you, wow!” It was very nice, of course.

I was waiting for an appeal at the Mahilou remand centre, where I was sharing a cell with a guy who was there on drug charges. He kept walking around and looking at me, but wouldn’t say anything. And then my wife sent me a letter that contained some printouts. There are some restrictions, right? You can only possess two photos, but the number of printouts from the Internet wasn’t limited. One of the printouts had a photo that’s often used in the articles to depict me. In it, I am standing on the street with a microphone, it’s wintertime. I was looking at this picture and this guy also saw it from behind and said, “So that’s why you seem so familiar to me! I saw you!”. I’d shaved off my moustache by then, so it was more difficult to recognise me.

Aleh and his wife Marianna are standing by his portrait at the exhibition of drawings by political prisoners. Courtesy photo

There was also an interesting situation in the correctional facility. In my unit, there is a room with a fridge, and there is a special person who controls knives and other things. I came in and he told me: “They say you are a famous journalist. What’s your name?… Oh, I know the name… Do you remember a story about a jewellery store robbery? I was the accomplice”. It’s funny because I wrote about this story! And now he lets me have the knives in prison.

But this famousness had another effect at the correctional facility. When I met the prison warden, he immediately shouted: “Oh, are you the Radio Liberty journalist? You are going straight to segregation! You’ll be held accountable for every one of your tribe”.

I didn’t have to deal with spiralling bad thoughts in prison. I was prepared for this a long time ago – I did a lot of writing about politics and crime and a lot of talking to politicians. I covered a lot of trials – both political and corruption – so I knew the different stages, I knew what was going on in prisons.

And my experience has shown that everything points to an intensification of repression. One day they would come for me.

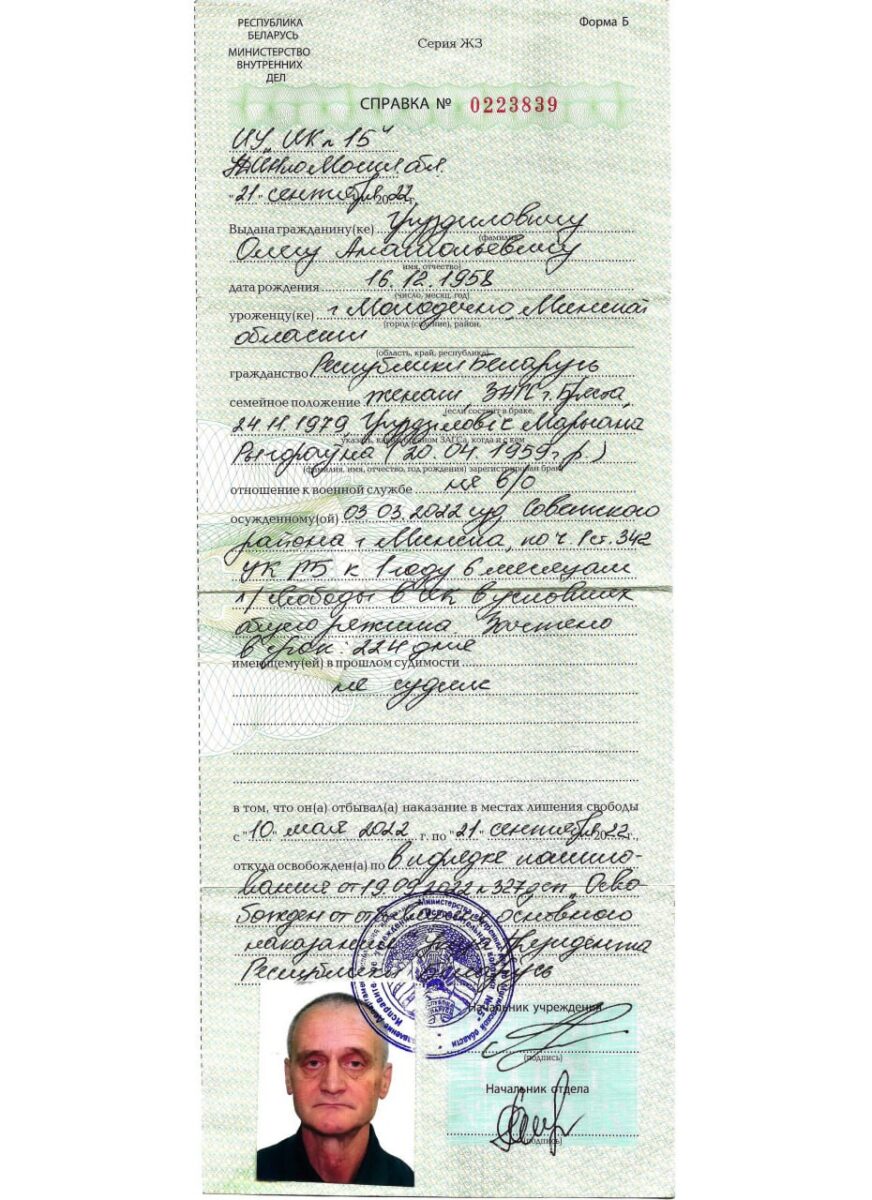

The first time I was held was in July 2021 with Ina Studzinskaya and Ales Dashchynski. We were sent to the temporary detention centre in Minsk, a criminal case was opened, and then we were released, but the case itself was still pending.

I was ready for it psychologically, so I didn’t have any hesitation or self-chastising like “Why did I get involved in this?” If you hadn’t moved on from this line of work, you had to get ready. Of course, I kind of hoped that I would get away with it, like any normal person.

Just a few days before my arrest in July, I realised that I hadn’t been able to swim once during the summer because I’d been so busy. I managed to find some time to go to a quite crowded reservoir. I was swimming and I noticed a man and his wife standing chest-deep in the water next to me. I could see them hanging out in the waves and the man looking back at me now and again. I was swimming past them again when he asked, “Are you from Radio Liberty?” I confirmed and stopped because I knew the usual conversation will start. He’d say that he and his wife were listening to the radio and are very grateful, and so on. But instead, he asked: “Tell me, why haven’t you been arrested yet?”

Forefathers’ Eve Day 2023. Aleh Hruzdzilovich at Vilnius’ Rasos Cemetery, near Frantsishak Alyakhnovich’s grave and monument. Last year, the journalist was awarded a prize named after the political figure for the best work of prison literature. Courtesy photo

It’s true that they recently arrested Nasha Niva, BelaPAN, and TUT.BY staff members. We joked about it and carried on with the conversation. They said that since Radio Liberty is an American media outlet, the authorities didn’t want to get involved until recently. And I still think that was the case.

But after a few days, we were arrested anyway. And the authorities were not ready to put the matter to rest. They dropped the curtain a few months later when the outlet was recognized as extremist. Just to let you know, I found out that the Radio Liberty Belarus website has been declared extremist by the police. When I was arrested on December 23 and brought to the remand centre, one of the police officers told me the news.

The general consensus is that my imprisonment was revenge for all my years of work. Apparently, the authorities had more grudge against me when they were deciding which of us to imprison. I think they had some inside info and knew that I’d actually been to a lot of protests.

Do I want to get even with them? Why would I? They’ve already taken care of it themselves. This is going to end badly for them, one way or another. This blob will eventually start to leak. I think we will return to the country. But if they have somewhere to return to, I am not sure.

In general, on that day, 23 December 2021, we were preparing for Christmas and I was busy at home hanging fairy lights on the windows. Meanwhile, I was cooking soup. At one point I left the house, looked at my windows, walked literally 50 metres away and remembered that I had forgotten to turn off the oven.

So on the way back, I got a call from Ina Studzinskaya asking if there was any news about our criminal case. I replied that everything was quiet, as usual, and I hadn’t heard from the law enforcers.

You know, it ended up like in the movies, when the hero says everything is fine and then gets hit by a car.

I approached the entrance and saw a young man standing there, looking at me like that guy in the reservoir. He asked me if my name is Hruzdzilovich, and I said it is, he grabbed my hands, there’s a commotion, we went into the stairwell, and Ina heard all this on the phone and thought they’ve raided my home. She heard something crashing, but it was me trying to open the front door myself.

Later they were unhappy about reports that my house had been raided. “Why are you writing this nonsense, nobody broke your door!” My wife called me when we were still at home, but they wouldn’t let me answer. They had a look at the name “Marianna” on the screen and asked who it was, and that was that. I told them later: “Well, you didn’t let us talk! I would have told my wife that everything was fine. Like, yeah, they arrested me, but no big deal”.

But they did have a car parked in front of my house with all the equipment that would have allowed them to break into the house. It just so happened that they met me outside, and they didn’t need to break in.

The imprisonment in itself is terrible, but acceptable conditions can be created there, too. Humans adapt…

We always have a reference point. People do not compare what they see inside with what they saw outside when they enter prison. They compare it to the situation in a remand centre. They end up in prison six months or even a year after their arrest.

The way it was on the outside… You don’t even dream about it anymore!

These are the conditions in which you have to survive. I’ve heard people say it’s a little easier in the remand centre than in the correctional facility. But it depends on what you assess. When it comes to food, it’s easier because you get care packages in a remand centre, and some people would get one three or four times a week. But from the perspective of free will and movement, it’s a different story. You don’t see the sun for months, and you can’t breathe and walk normally. There were eight people in my cell, and we were pushed into a box that was two by three metres. You are literally just walking on people there.

At night, you sleep on a bed with no springs, just metal strips that are usually hollowed. And the mattresses leave much to be desired. I once saw a better mattress in the warehouse and thought I’d take it, but they told me, “No, don’t touch it, this one is for women”. I got an old, terrible mattress that made it difficult for me to get a good night’s sleep.

And all this builds up. You’re also waiting for the indictment, the trial, the sentence… What will be your verdict? What would be the final charges? Then you wait for the appeal…

When I got to the correctional facility after all this, I was taken to the showers after the quarantine period. I walked around this prison town and I was so happy as if I was in the Maldives. It was May, and the sun was shining. People were walking around, and you could see people in the windows. Some construction workers were wearing normal clothes. They led me past the stadium, where I saw men playing football in their underwear, like gladiators.

When you get to the facility, you usually see the plus sides, but then you realise there are lots of drawbacks compared to the remand centre. One serious threat is the punishment cell. After that, the risks are the Secure Housing Unit, high-security prison, new charges and new terms.

In a remand centre, you’re stuck in a cell with other people, and you form relationships with them. It’s like an ecosystem. Once you get to the facility, you’re thrown into the unit, and the rules are already in place. It’s like you’re a child again.

The prison warden once told me that I should “stop my intelligence activities”. And he didn’t say it without a reason – shortly before they found a notebook in which I described the barracks, among other things. And they understood that I don’t just write letters about how I am doing, but note very precise descriptions, like “20 metres long, 5 metres wide”.

I just wanted to keep it all in my head, because I knew I would have to write a book about it. I prepared myself in this way from the beginning.

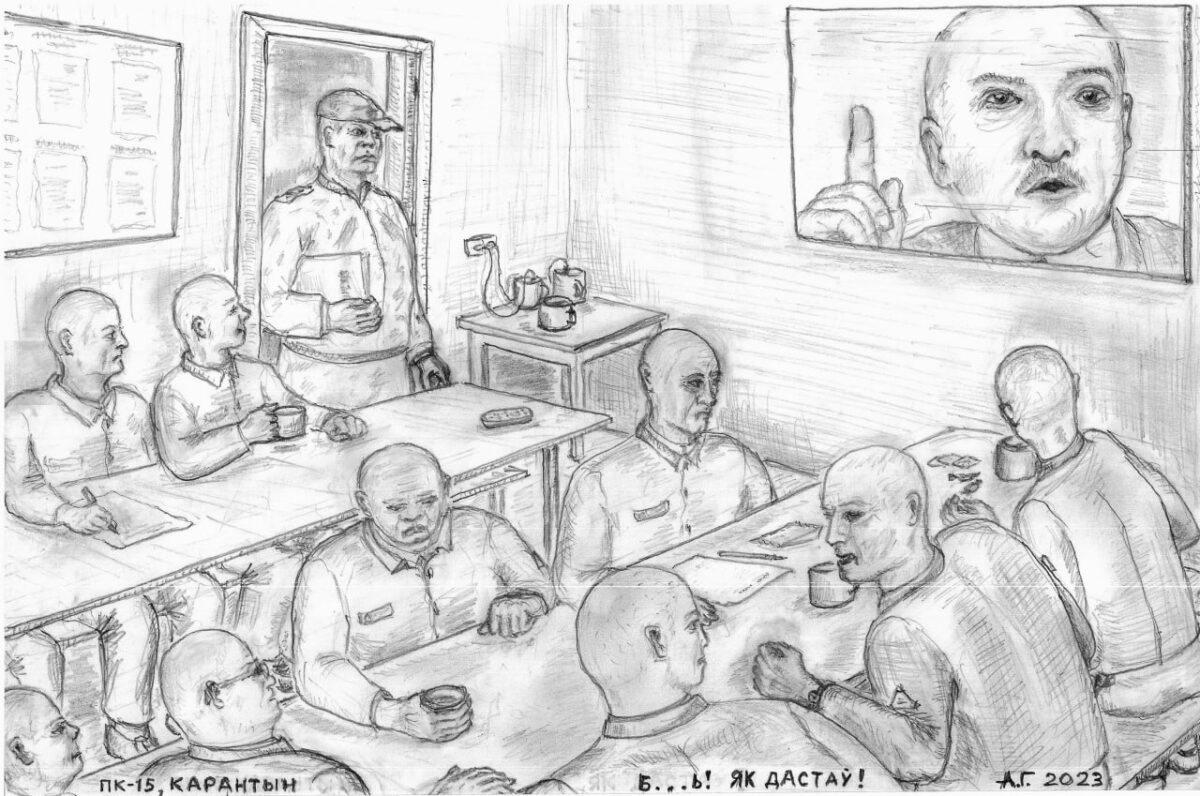

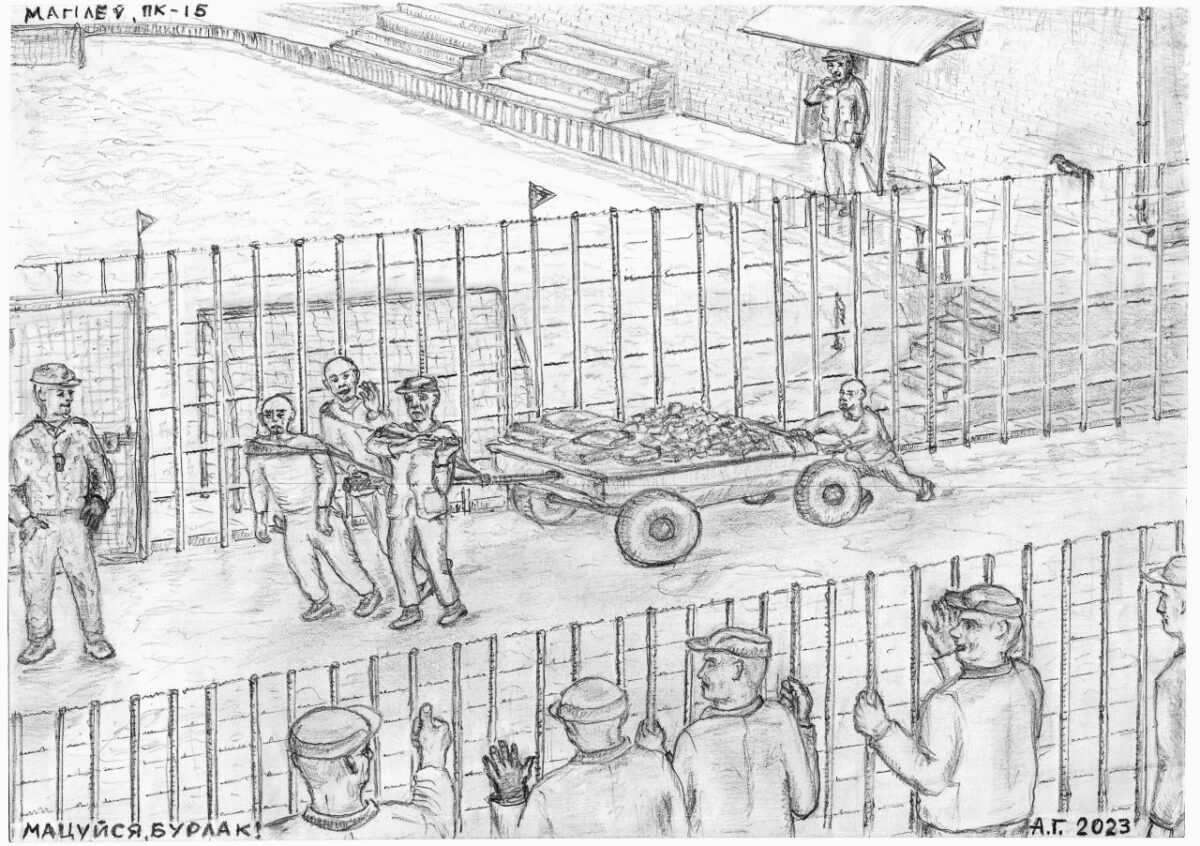

Drawing by Aleh Hruzdzilovich. Courtesy photo

When I was taken from the punishment cell to the unit, I would walk around and look at what I thought was interesting and worth remembering and what I thought was not.

I started drawing a lot in prison. When you draw, you have to notice a lot of details. I also met a guy at Mahilou remand centre who was quite talented at drawing, but he worked very slowly. In prison, you usually just get someone to give you a photo of their wife and say, “Here, draw it”. So you just sit there and draw.

I’ve done this a few times and it usually took me about an hour or two. And he was really slow. One day, while he was in the middle of a drawing, I did a drawing of him. He was amazed that I could do it so accurately and so quickly. I told him he had to develop his visual memory, we had a bit of a chat about that. After some time we were taken for exercise and I asked him: “What was in the hall, what do you remember?” But he remembered nothing. “What do you remember about the stairs?” He couldn’t recollect anything.

Drawing by Aleh Hruzdzilovich. Courtesy photo

So we started training our memory together. Of course, we did it all secretly. I get that if you start talking about the prison, people outside might think you’re planning an escape. There are snitches all around! If a snitch tells the operative that these two discuss things like how many steps there are, what colour the walls are…

I used to send home poems with illustrations when I was in the Minsk remand centre. At some point, they stopped reaching my family. And then one day I got back my drawing of the cell door with all the details – the peephole, the scratches. The censor made a note that I was not allowed to draw anything from inside the prison. If I drew something about the exercise yard, it would pass through the censors without any problem, as if the yard was not part of the prison.

Then it all helped me in writing the book.

As for the “before and after” photos when a person is released from prison… I think there is nothing unethical about it, quite the opposite – everyone sees and understands what is happening. People don’t just see what a person looks like now, they remember what they looked like before they were imprisoned. I have been compared to old pictures, to the live broadcast records that I have done.

It just hurts to hear someone say, “Oh now you’re finally normal, you looked terrible upon release!”

Especially if physically, I felt fine. When I came out of prison I used to do 10 pull-ups and now I can’t do them anymore.

There is a downside. Sometimes we see an article about someone who has been sentenced to a long prison term, and there is an old picture of them, and they look good and they are smiling. This is confusing. Journalists have to use file photos, but now the person is completely different and in different circumstances: they are no longer smiling and are having a hard time.

Courtesy photo

Because we simply do not and cannot have fresh images, we are forced to accompany brutal information with images that no longer reflect reality.

My wife is often outraged because underneath the article saying that the person has been sentenced to 10 years, there is a photo of that person looking happy.

Because there is no way to get a current photo, we take old photos. And I don’t see a solution to this problem. Perhaps it would be a good idea to add a note saying when and under what circumstances the picture was taken.

Terms and conditions

Partial or full reprint is permitted subject to following terms of use.

An active direct hyperlink to the original publication is required. The link must be placed in the header of the reprinted material, in the lead or the first paragraph.

Reprints, whether in full or in part, must not make changes to the text, titles, or copyrighted photographs.

When reprinting materials from this page, attribution must be given to the Press Club Belarus “Press under Pressure” project, collecting evidence of repression against independent media and journalists in Belarus.