A few months later, on December 23, 2021, Hruzdzilovich was taken from his home in Minsk by unknown masked people. His pre-trial restraint was changed and the journalist was taken into custody. Five days later, it became clear he was accused of participating in an unauthorized rally after the Belarusian MFA revoked his accreditation.

In March 2022, Hruzdzilovich was sentenced to 18 months in prison. The journalist was a political prisoner and served his sentence at Mogilev prison No. 15. At the beginning of July 2022, Minsktrans [Minsk Transport Agency] served Aleh with three civil suits for interruption of transport operation during rallies in the summer and autumn 2020, for a total amount of over 56 thousand Belarusian Roubles.

On September 21, 2022, news broke that Aleh Hruzdzilovich and his wife Mariana were in Vilnius. He told his colleagues from Radio Liberty that he submitted a petition for pardon but didn’t plead guilty. The condition for his release was that he left the country to which Aleh responded with his own condition that he would only leave with his wife. Aleh also said, ‘Only their argument that my colleagues might not be released, if I refused, assured me. Another argument was that my detention might be extended from 18 months to a much longer time. All these worked and I decided to agree to leave.’

On November 4, 2022, the Ministry of Internal Affairs added the journalist to the list of persons involved in extremist activities. Released on September 2022.

Aleh Hruzdzilovich’s story is told by his friends, colleagues and wife.

Aleh Hruzdzilovich worked at Znamya Yunosti newspaper at the end of the 1980s – the beginning of the 1990s. We knew each other because everyone working for different newspapers at the House of Print used to meet at least once a week to play football. He was a nice football player, a sports person, very strong, active and smart.

However, I got to know Aleh for real during the Communist coup in the autumn of 1991. It was when Znamya Yunosti, where Aleh was the executive secretary, refused to publish the GKChP [State Committee of the State Emergency] statement. It was a brave political act. Aliaksandr Klaskouski, Ales Lipai shared his position. Since then, Aleh’s political and personal portrait was complete for me.

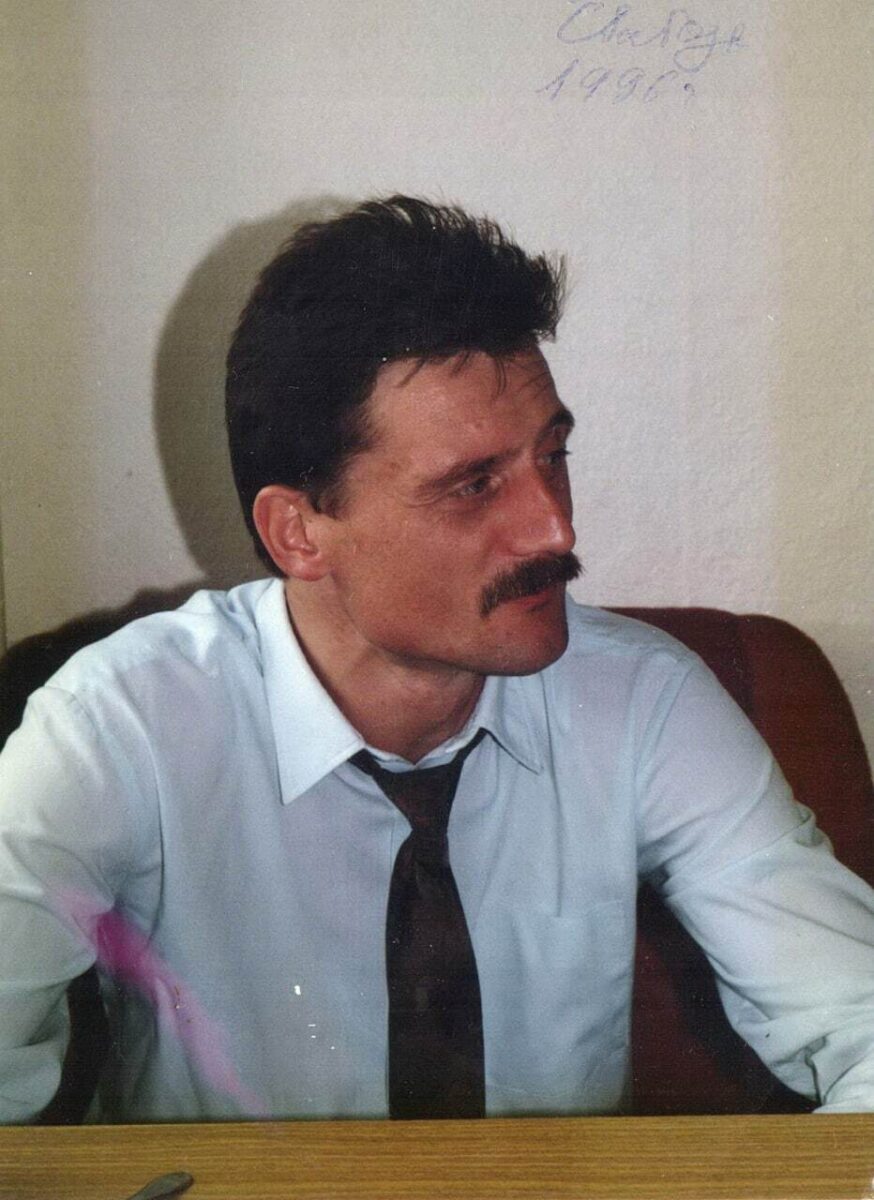

Aleh Hruzdzilovich at work, 1996

This act illustrated Aleh’s main traits. First of all, as a journalist, he is fearless. He worked with the law enforcement system, courts, police, KGB. When Aleh received an editorial assignment in this sphere, he went into the thick of action.

I remember those videos from the silent protest rallies [decentralised rallies in 2011 when the protesters went to the central squares of their cities] when he came up to a police officer and asked a question and was immediately attacked by the military bearing people in civilian clothes and carried away. They carried him holding him up over the ground while Aleh repeated just the same words, ‘I am a journalist, I’m on editorial assignment. I’m a journalist.’ That was a powerful scene.

Another thing I noticed about him was that he went to the end when studying materials. He was assigned as the lead reporter on the case of the explosion in the Minsk metro. Reporting was one part of his assignment and court proceedings was the other.

Those were open proceedings which allowed journalists to be there. Dozens of journalists attended but only Aleh wrote a book, ‘Who is behind the explosion in the Minsk Metro’. It started as daily reports from the courtroom and grew into a lot more: talks with experts from Europe and Russia, counter-terrorist experts, with psychologists, with the people who knew the main suspects, attentive listening to the witnesses and statement of the official version.

This was a many-sided professional work corresponding to the latest Western standards of a documentary investigation. Look at the title. The author does not make a statement, he is raising a question, ‘Who is behind the explosion in the Minsk Metro’. The whole book, all the materials are about that. Why were the proceedings open? There were witness statements… Yet still, the court in this country is not the way to seek truth. While journalism is such a way for Aleh.

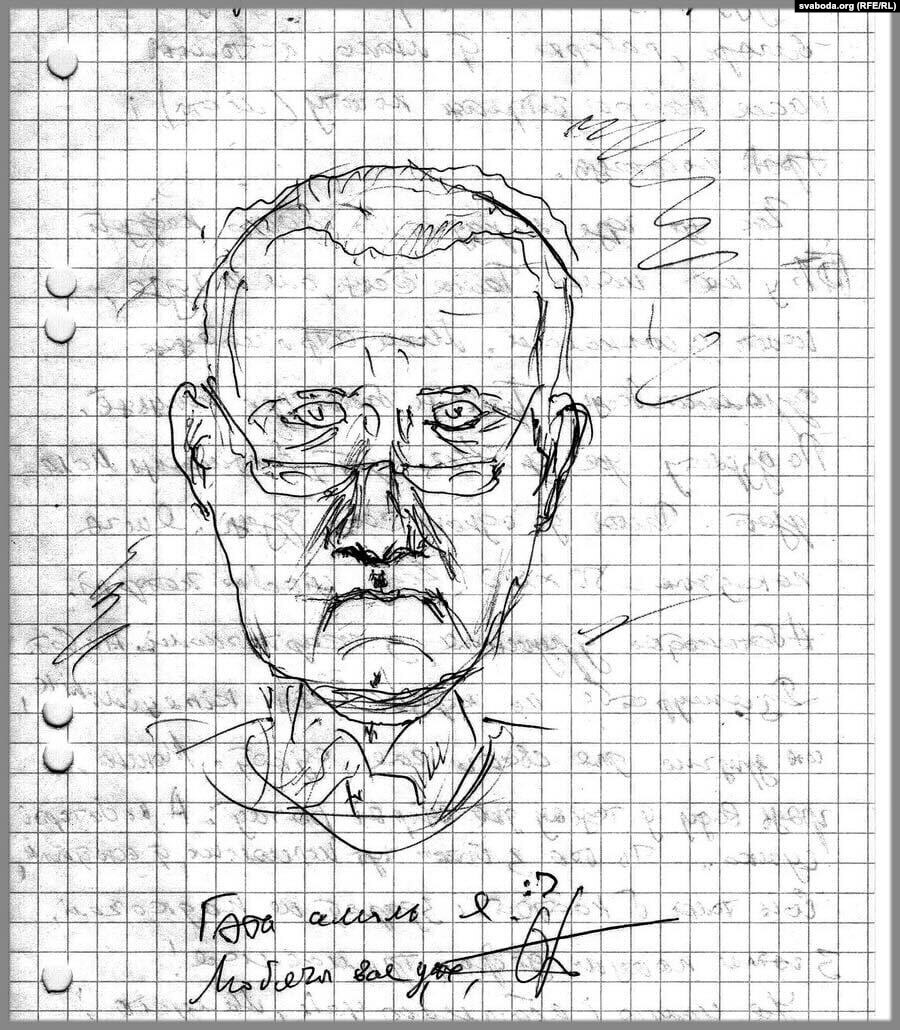

Aleh Hruzdzilovich

He is a bit older than the average age in our editorial office. Yet how easy he was with everyone, how experienced, how he respected his colleagues – all these created an impression of him as a soft and respected person. When we found out his hobby was to build ship models and reconstruct old ones, it fit very well into the picture.

When Siarhei Hadzhankou died, a famous Soviet political prisoner [he was arrested for an attempted explosion of jamming stations in Minsk] and the Radio Liberty listener, his family gave us a huge Minsk-55 receiver. With this received, Hadzhankou used to listen to Radio Liberty in the late 1950s – early 1960s. I saw the device at his flat when I visited and it was in a bad shape. So, Aleh took it home and renovated it with such love and care that the receiver looked better than new.

We made a special place for it in our office as a reminder about our audience, our listeners and how we should remember and respect and cherish them. It was Aleh’s doing. We managed to save the receiver after our office was destroyed by the police.

Why did they open a case against him? The full list of journalists, employees of the Belarusian media who are now imprisoned is published on our website under one title, ‘Imprisoned because they are journalists’. This is a short yet exhausting answer to the question.

Self-portrait from prison

We were classmates. I was born in Russia and when I was in the sixth grade, we moved to Brest, Belarus. Because I studied at a specialised English language school, my mother found the same for me here. It was newly built and had a swimming pool which was very cool for that time.

I got into class 6A and took notice of the Belarusian names which sounded unusual for me. So once they said, ‘Hruzdzilovich’, and a boy came up to the blackboard. Then again, ‘Hruzdzilovich’, and another boy stood up. As I figured out later, I was in the same class with twin brothers, Aleh and his brother Siarhei.

I started to like him in the ninth grade but didn’t show it. We cleared up later that he liked me, too, but said nothing. Our prom was on 25 June, like in the rest of the Soviet Union, and there was a local tradition in Brest to have a celebration for the graduates in the central park the day before, 24 June.

Our whole class went to the ‘Boats’ swings first. We formed a line there and I noticed that my turn would be with Aleh’s brother while Aleh himself was standing in the distance looking at the racetrack. I figured it out and made probably the most important steps in my life within seconds: I pulled myself together and approached Aleh saying as casually as I could, ‘Aleh, let’s swing in a boat together!’ He turned to me and agreed.

Our prom was the next day and I was anxious to know whether Aleh was serious about us or it was just one time. So I was nervous and then the first slow dance started and while there was still nobody on the floor, Aleh crossed the hall and asked me to dance with him in front of all the pupils, parents and teachers. Then while we were dancing, he told me his feelings were serious which made me happy. That’s how our love story began.

We became political in the early 1990s. I knew nothing about those things. I remember Zianon Pazniak and Belarusian People’s Front appeared. There was a big rally in Serabranka [a district in Minsk] where I saw the white-red-white flags for the first time, and Aleh already knew all that. I remember us going to that rally with our three children.

Aleh was a parliamentary reporter. It was the 1994 presidential election in Belarus and they were airing the debates of the candidates on TV. It was the first time I got interested in politics. Aleh explained to me we should vote for Pazniak. Since then, Aleh and I have been fellow thinkers.

Journalism is the most important thing in Aleh’s life. He has been a journalist forever.

He started out at Znamya Yunosti, Narodnaya Volya, Ihar Hermenchuk’s Svaboda. Later, Zhanna Litvina invited him to the Belarusian Radio Liberty and he has worked there for 30 years.

Aleh considers his team at Radio Liberty his family. They respect him there. Journalism is his life. His topics were political prisoners, talks to their families; he spent a lot of time in courts. He was very responsible about those articles and got devastated if rare errors occurred, apologized to the families.

Aleh feels very responsible about everything in his journalistic work and doesn’t allow lies or offensive language. He is very considerate, a true professional.

Some people tell me not to worry because Aleh got a considerably short term (many others got more). But these words don’t help, they offend me. I feel for everyone unjustly accused and worry for them, but this sentence feels like eternity for us! We’ve never been apart for a long time. And now we are forced to suffer alone, damaging our health and not seeing our family, and all that for doing nothing against the law. So one should never tell families of the imprisoned that they are lucky to be sentenced for a short term. There’s no joy in it. Aleh and I miss each other and are very anxious to finally meet outside.

I am very lucky to have met him. And I am very grateful. I cherish him because Aleh is a decent man and a true citizen of his country!

I’ve already heard about Aleh when I was still at uni. I’m a bit older, but all the groups were small so everyone knew each other. In 1988, there was an earthquake in Spitak, Armenia. A small group of Belarusian journalists headed there, Aleh among them [there were no women, even though we wanted to go].

It was a great challenge. The city was almost completely ruined, so they worked both as journalists and helped to clear debris. I read a lot of Aleh’s articles later in Znamya Yunosti. Everyone used to read newspapers all the time; papers hardly fitted into your mailbox when you checked it in the mornings. Everyone was reading on their way to work, I took newspapers to work to read.

Once I was looking for the texts about the first marches on Kurapaty and other events like that. It was a long time ago when the National Library was moving to a new building. I was sitting at the academic library – they had a very convenient newspaper department – and I just couldn’t stop reading my colleagues’ articles. 1988 to 1989, I was very curious what they were writing and how. And Aleh’s reports from Spitak made me burst into tears again, so touching they were.

I was also moved by the perestroika interview Aleh made with now People’s Artist Viktar Manaev, who was in the early days of his career back then. It was great to see how a professional could find proper good questions. That interview was a good one.

Then he was one of the first to leave the state-owned press to work at Ihar Hermenchuk’s newspaper Svaboda. It was so cool, so honorable. Aleh left a considerably favourable position at Znamya Yunosti and moved to independent journalism among the first to do so.

The Hruzdzilovich family

He took his imprisonment for a protest rally very courageously. He was accused of having no accreditation even though he had Narodnaya Volya credentials. I wrote him letters while he served his time in Baranavichy. He described the horrible conditions in prison at the beginning of the century, his cell mates. But always with a hint of humour. He was extremely courageous under such harsh circumstances.

He is fond of two things: one is history – he would dive into the greatest depth, so educated he is and so much he knows. And the other one is, he used to buy ship model parts in Belsayuzdruk kiosks and build ships. I have no idea how many thousands of pieces there were. He was building them for several years. All parts glued perfectly to each other, fit evenly well, such precise work. I can’t imagine how patient one needs to be. He brought a finished ship to the office once and his home-made wine and we all celebrated.

He is very stubborn. Once he started digging, he wouldn’t stop until he got to the bottom of things. When the state officials cooperated, he bombarded them with calls and questions reaching to the truth. He is annoying in a good sense. And he is difficult to argue with because he proves his point emotionally.

Aleh Hruzdzilovich’s hobby requires patience and skill

We are ‘partners in crime’. They came to the four of us in July 2021: me, Ales Dashchynski, Aleh Hruzdzilovich and Valiantsin Zhdanok. Zhdanok wasn’t at home but they took the rest of us. We served ten days each and were released; Hruzdzilovich was released just a half an hour after me.

Nothing happened. No questioning, nothing. We remained suspects. I’m still very much curious about why they took us and what we are accused of. I can’t say we spoke often, but on 23 December, in the evening, we did. That day, Svaboda was recognized as extremist, among the last media, and Andrei Kuznechik’s case was made a criminal one.

I called Aleh at 5 pm sharp. ‘Hi, how are you? How do you like the news?’ We talked for a minute or so and then I heard loud noises, men speaking and Aleh asked, ‘What’s going on? Who are you?’ And we were disconnected. I just sat on my sofa for five minutes, then I took my backpack and left silently. I haven’t been home since.

We came to a subjective conclusion that they retaliated for all the years of Aleh’s work. Both his and Radio Liberty’s because he reported from courtrooms, from rallies. We hoped for open type detention knowing they wouldn’t leave things be. There were no legal grounds. He worked when we had accreditation, it was completely legal.

Aleh worked at all the rallies in 2020 until his accreditation was revoked. He was in the most difficult situations. He continued to report events by phone even under explosions, grenades, from the avant-garde of the events, without hiding or running. He streamed live videos while we still could. He was detained during one of those. I can say he was one of the bravest and most successful journalists covering the 2020 events.

After being detained he spent 15 days at a pre-trial detention Centre in Baranavichy. It was hard for him. He caught COVID-19 there and spent days in bed without proper treatment. He returned worn out and tired.

When our accreditation was revoked, he still worked as an outstaff reporter for Narodnaya Volya. It was legal. He went to the rallies and covered events there. This became the grounds for a criminal case against Aleh and our other colleagues.

He was a journalist at those rallies, so they punished him literally for his journalistic work. It is a completely fake case and the sentence he received is unjust and politically motivated. In his final statement, Aleh said great words about the freedom of speech being under pressure in Belarus.

Understanding that he is suffering for justice, for freedom, for Belarus helps him get through these hardships. According to his letters, he is holding up, he’s not broken.

Terms and conditions

Partial or full reprint is permitted subject to following terms of use.

An active direct hyperlink to the original publication is required. The link must be placed in the header of the reprinted material, in the lead or the first paragraph.

Reprints, whether in full or in part, must not make changes to the text, titles, or copyrighted photographs.

When reprinting materials from this page, attribution must be given to the Press Club Belarus “Press under Pressure” project, collecting evidence of repression against independent media and journalists in Belarus.