What has happened to the Belarusian media and journalists since the day of the presidential elections — from 9 August 2020 until today — is an unprecedented case of the eradication of independent journalism in a single country, in the centre of Europe, in the 21st century.

Despite the measures taken by the authorities, we can say that independent Belarusian media continue their work, even in exile. But a high price is paid for it: the journalists are in jail, some have already served their time and been released, and some are sentenced to new terms. Many editorial boards have left Belarus in order to provide independent coverage of Belarusian and world events. Those who stayed were forced to avoid the socio-political agenda.

Detention of journalists in Belarus continues. Since the beginning of 2024, at least 10 journalists, whose names were made public, have been detained, but the total number is at least 26 individuals. At least 60 property searches have been carried out. This data was provided by the Belarusian Association of Journalists).

The number of unreported and anonymous cases is increasing. In reality, the situation is even worse than the statistics would suggest. Now the police are coming for every media worker they can find in the country, including those who have worked with independent media at least once, as well as those who were employed by state media at the time of their arrest.

In contrast to previous years, when the majority of cases involved detentions and arrests, this year has seen a notable increase in searches at the registration addresses of exiled journalists. The logging of cases of repression is becoming increasingly challenging, and the figures may suggest a decline in prevalence. However, this may be due to a reluctance among individuals to publicise such incidents.

The prosecutions continue. As of the end of 2024, at least 45 media workers remained in prisons and remand centres.

A terrifying figure: over 4 years, journalists were sentenced to a total of 247 years and 2 months in prison.

Journalists have been included in the group of people subjected to “remote” prosecution. 11 journalists were prosecuted and tried in absentia. In July 2024, the Minsk Regional Court heard the cases of 20 people whom the Belarusian Ministry of the Interior described as an “extremist formation” called “Sviatlana Tikhanouskaya’s Analysts”. This list includes two journalists – Yury Drakakhrust and Hanna Lubakova. They were condemned in absentia to 10 years in prison each.

This year has also seen an increase in the persecution of exiled journalists. Over property 60 searches have been reported, including at the residences of exiled media workers and the homes of their relatives remaining in Belarus. Some have had their property confiscated. Legal proceedings in absentia and special criminal proceedings have been initiated against them.

Some imprisoned media workers who completed their sentences have not been released. On 28 November, vlogger Dzmitry Kazlou (known as «Seryi Kot») was not freed after four and a half years in prison. He was promptly sentenced to an additional term, allegedly for persistent disobedience to the prison administration (Article 411 of the Criminal Code). Reports suggest his sentence was extended by one year.

Similarly, on 11 December, journalist Ihar Karnei, who had been sentenced to three years, faced the same charge. Judge A. Tarakanau sentenced him to additional eight months of imprisonment under Article 411.

In 2024, some imprisoned journalists have been released, either after serving their full sentences or through pardons. Among those pardoned are former state TV journalists Ksenia Lutskina and Dzmitry Luksha, as well as cameraman Andrei Tolchyn, who was re-detained on administrative charges two and a half months after his release.

The practice of criminalizing media consumption persists, with authorities continuing to pursue legal action for “promoting extremist activity”. This has resulted in the imposition of penalties for a range of online activities, including sharing, commenting, following, and liking.

The authorities keep restricting access to independent media outlets from Belarus. In April 2024, following court rulings, the authorities seized a number of domain names belonging to publications on the Republican List of Extremist Resources. However, many newsrooms have cautiously migrated to new domain names.

The media outlets continue to be classified as “extremist formations and organizations”. At least 35 media outlets and media projects have been given the status of “extremist” by various orders, and the list is still growing.

The search for new “extremists” has been churned out. The authorities first recognise publications as “extremist” and then assign the appropriate status to the whole media outlet/project. For example, in just six months in 2024, the Brest Regional Prosecutor’s Office alone reported that it had “identified” almost 200 “extremist” resources. In Homel, in just one and a half years (since 2023), the prosecutor’s office has initiated the recognition of more than 90 media projects, as well as social media accounts and Telegram channels, as “extremist”.

All resources and media outlets classified as “extremist” pose a significant risk to journalists who worked on these projects until 2020 and subsequently left the profession but remain in Belarus.

All periodical media outlets and leaders in the field of socio-political content creation are already designated as “extremist formations”. The vast majority of independent media outlets have been designated as “extremist” entities, their websites have been blocked, and the dissemination of their publications has been criminalised.

And yet there is a readership of independent media in Belarus. The results of sociological surveys indicate that the loyal audience represents the core of the share of Belarusians who are interested in public and political information, with figures standing at 17.1% in 2022 and 13.4% in 2023.

The audience in Belarus keeps providing extensive feedback. This is evidenced by our media survey. For instance, 87% of media outlets generate their content based on information from readers (user-generated content), with some producing up to 30-50 such pieces per month.

Independent media is flexible in responding to challenges. In the face of intensifying pressure from the Belarusian authorities, which has included the designation of the majority of independent media as “extremist”, the blocking of websites, and the criminal prosecution of journalists and audiences, the media have adapted their strategies for content distribution and interaction with the audience. They have also reached their readers through various channels, including with the help of proxy services.

Information is being increasingly controlled: even bloggers now need to be registered and monitored. As of 12 July 2024, legal entities and individuals are prohibited from placing advertisements on the Internet unless they are registered in the State Register of Advertisers.

Belarusian independent media and those working in the media continue to relocate. Poland, with Lithuania in second place, currently hosts the largest number of media projects. A third of the newsrooms surveyed said that some of their staff remained in Belarus.

In 2024, another wave of migration of Belarusian media workers is expected to begin – from Georgia to EU countries. The conditions for the regularisation of the stay of exiled journalists have worsened following the inability to obtain or renew a Belarusian passport outside Belarus, as well as the enactment of the Georgian Law on Transparency of Foreign Influence. While the Georgian “foreign agents act” does not directly impact Belarusian media or freelance journalists, the deterioration of Georgia’s relations with the EU and the USA may pose a potential risk for journalists facing persecution for political reasons.

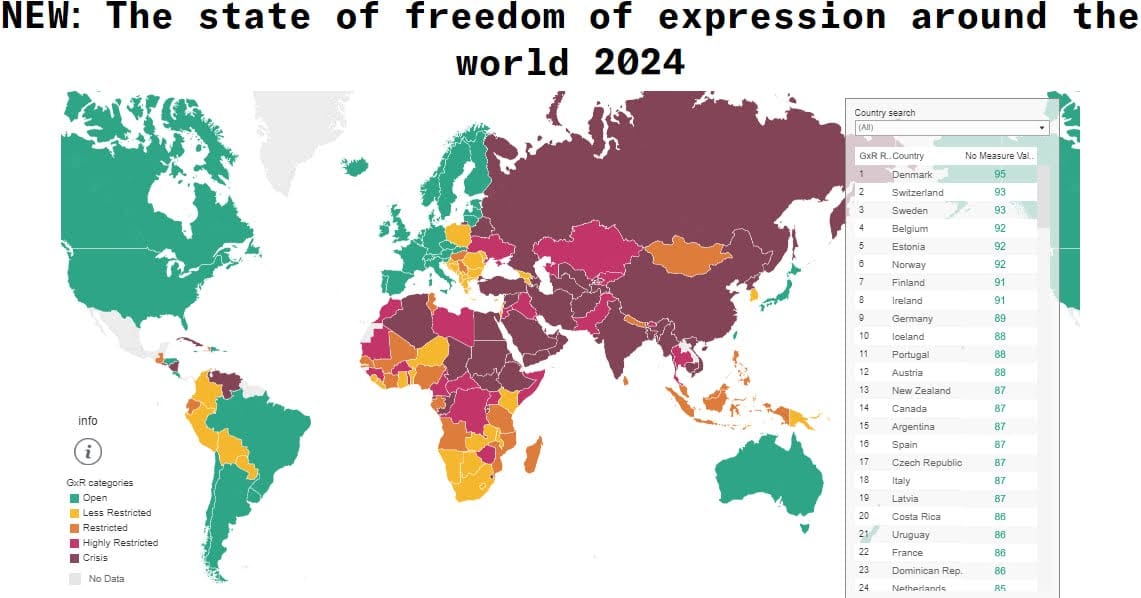

In the global ranking of freedom of expression, Belarus occupies the 158th position out of 161 countries. This is according to a report by the human rights organization Article 19. Article 19 evaluated 25 key factors that are indicative of freedom of expression.

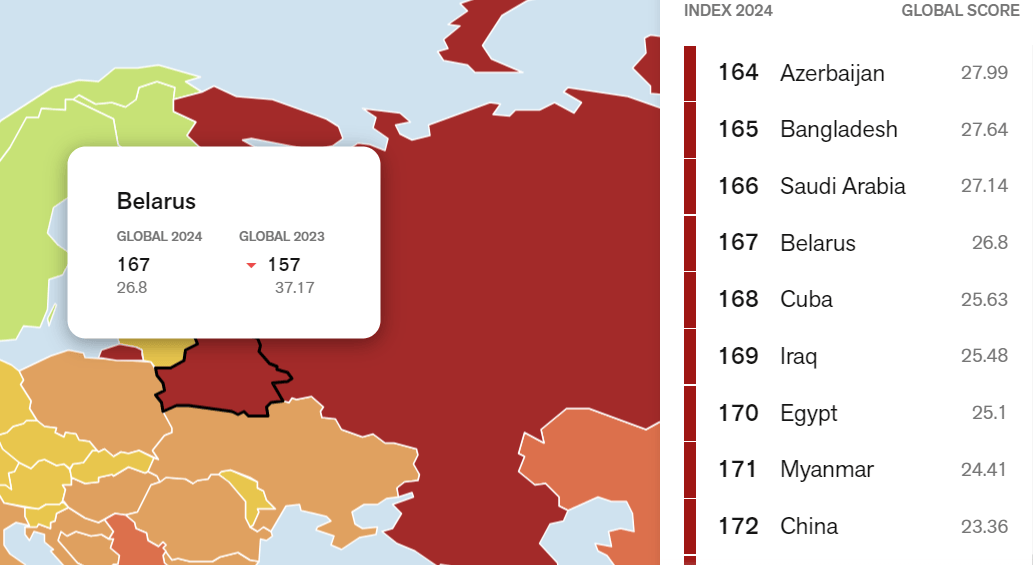

The World Press Freedom Index shows that Belarus is continuing to lose ground. The latest report from Reporters Without Borders reveals a decline of 10 points in Belarus’ ranking over the past year, placing the country in 167th position out of 180. Belarus remains in the “red” zone, with just 13 points away from the index’s low.

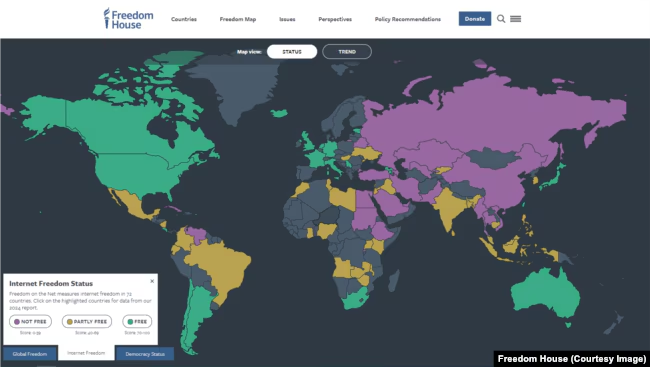

Belarus’s standing in the global Freedom on the Net Index for 2024 has declined. The Freedom House annual report, Freedom on the Net 2024: The Struggle for Trust Online, notes a significant deterioration in internet freedom in Belarus, with a score drop of three points. The country is now on par with Iraq and Zimbabwe.

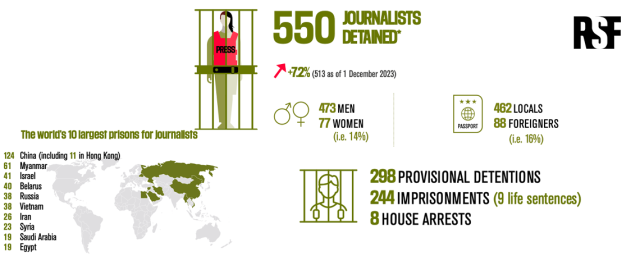

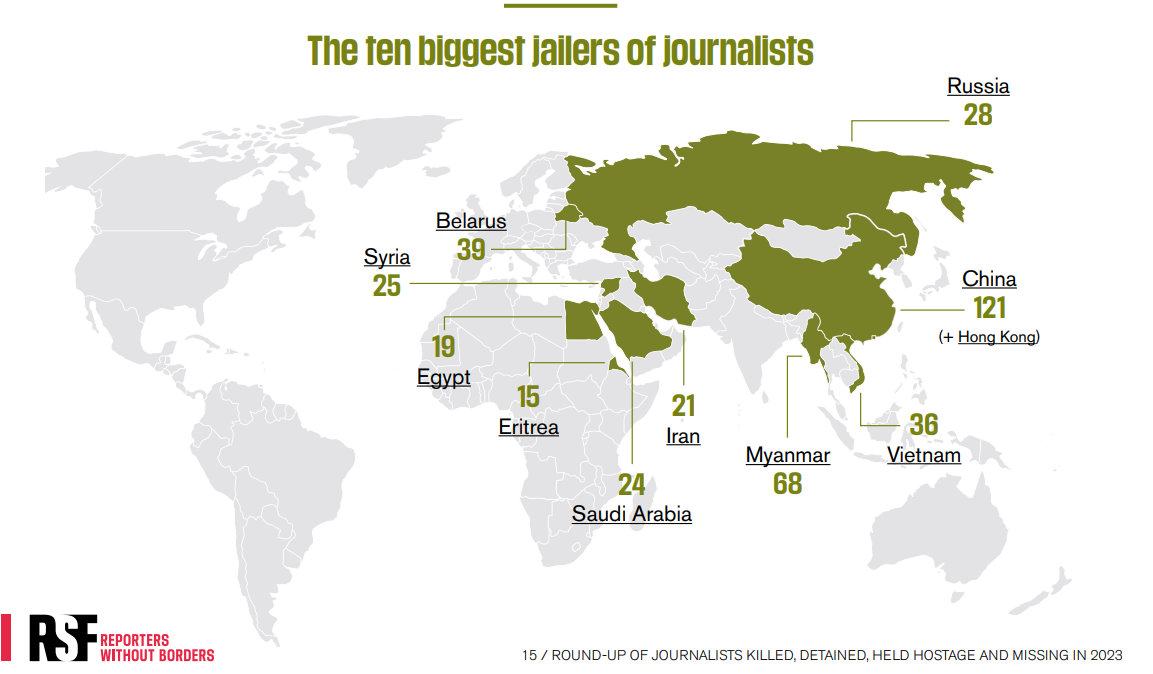

Belarus ranks fourth globally for the number of imprisoned journalists, according to the annual report by Reporters Without Borders (RSF). Only China, Myanmar, and Israel surpass Belarus. RSF data indicates that 40 journalists were imprisoned in Belarus in 2024, compared to 39 in 2023, when the country ranked third globally.

The situation continues to worsen. Shortly after the RSF report was published, seven employees of the previously terminated newspaper Intex-press were arrested in Baranavichy under Article 361-4 of the Criminal Code (facilitating extremist activity).

Belarusian journalists are gaining international recognition and awards:

Maryna Zolatava received the Palm-Preis in Germany, awarded biennially to individuals or organisations demonstrating exceptional commitment to freedom of expression and press freedom. In 2024, Zolatava was honoured alongside ZanTimes, a human rights website in Afghanistan.

Larysa Shchyrakova was awarded the Free Media Awards 2024 in Norway. The prize recognises journalists and media outlets in Eastern and Central Europe and is a project of the Fritt Ord Foundation in Norway and the Zeit Stiftung Bucerius Foundation in Germany. The prize is awarded for outstanding investigative journalism and personal courage at a time of great upheaval in the region. Some of the laureates are in prison for their journalistic work.

Hanna Liubakova received the Media Freedom Award at the Media Freedom Conference organised by the Transatlantic Leadership Network (Washington).

Andrzej Poczobut was named «Journalist of the Year» at Poland’s Grand Press Awards, the country’s largest journalism competition.

Anastasia Boika, editor-in-chief of Mediazona Belarus, was presented with the Hope for Freedom award during the Free Journalism Forum in Lithuania’s parliament.

Many journalists who have faced repression or imprisonment have left Belarus and return to the profession. One journalist remarked in an interview:

“It’s incredibly difficult to leave the profession when you’ve suffered so much for it. But it’s essential to understand that those who remain in Belarusian journalism are retraumatised daily”.

Many journalists have experienced repression themselves and now cover harrowing subjects, including torture and the inhumane treatment of political prisoners.

Detentions of journalists continued. 16 journalists were arrested between January and May 2023. As of the end of 2023, the Belarusian Association of Journalists reported 46 arrests, 34 searches and inspections of premises, and 16 administrative detentions.

Belarus has become the third country in the world to incarcerate the greatest number of journalists. The 2023 Report from Reporters Without Borders indicates that 39 journalists were imprisoned in the country in 2023 (including those who have already served their sentences and been released). 32 journalists are currently being held in detention, which represents an increase of 7 (!) compared to the number in detention in 2022.

Belarus became the world’s leading jailer of female journalists (10 women). China is just behind with 14 imprisoned female journalists.

However, when these figures are correlated with the number of countries’ populations and the relatively small total number of Belarusian journalists, the situation is clearly untenable.

Prosecutions are ongoing. Trials are closed to the public. In the “TUT.BY case”, Ludmila Chekina, general director of TUT.BY MEDIA, and Maryna Zolatava, the outlet’s editor-in-chief, were sentenced to 12 years in prison for “tax evasion”, “incitement to racial, national, religious or other social enmity”, and “encouraging actions aimed at harming national security”.

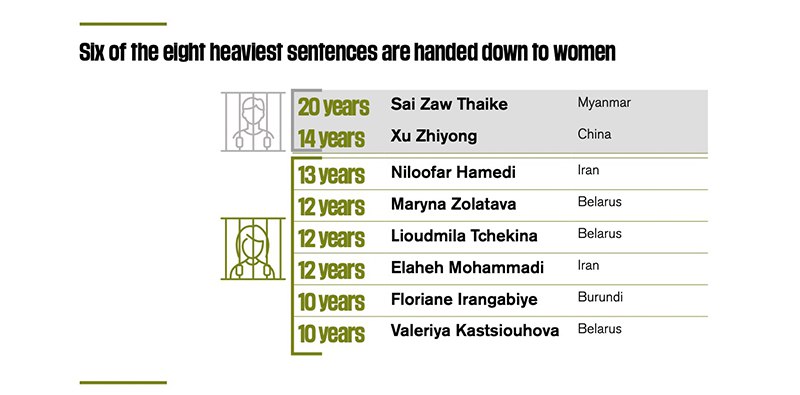

Belarusian female journalists received three of the six harshest sentences in the world. Maryna Zolatava (12 years in prison), Ludmila Chekina (12 years), and Valeria Kastsiuhova (10 years) made it to the world’s prison top 6. You can hear their professional voices on selected file videos.

In addition, a criminal case was filed against the organizers and participants of the “We Care!” charity marathon in solidarity with political prisoners for allegedly financing extremist activities. Sixty people are suspects in the case. The marathon occurred on 29 July 2023, with more than 20 independent media outlets participating. The event raised more than 570,000 euros for political prisoners and their families. Reflexions on the solidarity event are available here.

New sentences were handed down in the criminal case involving Larysa Shchyrakova, a former employee of Belsat, and her former colleague Viachaslau Lazarau. Shchyrakova, who had left the profession at the time of her detention, was sentenced to 3.5 years in prison, while Lazarau received a sentence of 5.5 years. Following an appeal in late November 2023, Lazarau’s sentence was modified to five years of incarceration, while his wife, Tatsiana Pytsko, was given a three-year suspended sentence with a suspension period of three years. This enabled her to care for her young child. A criminal case has been initiated against freelance journalist Andrei Tolchyn for his cooperation with Belsat. The charges are based on Article 361-1 of the Criminal Code, which pertains to the establishment or participation in an extremist organization.

Aliaksandr Mantsevich, the editor-in-chief of the Rehijanalnaja Hazeta (Maladzechna), has been sentenced to four years’ imprisonment and fined 14,800 Belarusian rubles (approximately 4,350 euros) under Article 369-1 of the Criminal Code for allegedly discrediting the country. His flaming final statement in court is available here. In December 2023, Aliaksandr Mantsevich was presented with the Journalist of the Year Award by human rights activists.

The media outlets continue to be classified as “extremist formations and organizations”. By May 2023, 14 media outlets and one media organization (the Belarusian Association of Journalists) had been designated as “extremist formations” in accordance with various orders. By the end of the year, 33 media representatives had been designated as “extremists,” and 12 more were classified as “terrorists.”

Any materials that are critical of the authorities are subject to repression. To illustrate, the Ranak TV channel was subject to a fine and arrests in connection with a coverage of an accident at a local enterprise. The Ministry of Information has kept restricting access to independent media outlets, including Plan B, Media IQ, report.by, and others.

The practice of criminalizing media consumption persists, with authorities continuing to pursue legal action for “promoting extremist activity”. This has resulted in the imposition of penalties for a range of online activities, including sharing, commenting, following, and liking.

Even bloggers with no political affiliation have been targeted by the authorities. Dzmitry Selviastruk, a sports blogger, and Aliaksandr Ihnatsiuk, the former editor of an independent regional newspaper, were charged with “promoting extremist activity”. In addition, several media personalities and well-known bloggers were arrested, including Hanna Bond, who was held for 15 days for “disobeying a police officer”, Larysa Hrybaliova and Dzianis Kurian.

Despite the challenging circumstances, there are indications of growth in Belarusian media projects. This includes Plan B, a venture established by former political prisoner Volha Loika, the new investigative media project Buro, and numerous others.

The work of Belarusian journalists is gaining recognition on the global stage. The Belarusian Investigative Centre and its director, Stanislau Ivashkevich, have been honoured with the Anti-Corruption Champions Award by the U.S. Department of State for their efforts in combating corruption. The editorial board of Reform.by has been honoured with a Free Media Award for its “exemplary coverage of the situation in Belarus under extremely challenging circumstances”. The Belarusian Association of Journalists has been presented with the Eastern Partnership Civil Society Forum Prize.

Detentions and searches of journalists continued.

Criminal persecution of journalists continued. Closed court hearings were held and media workers were given long prison sentences. Belsat journalist Katerina Andreeva was tried for the second time while serving a two-year prison sentence. Six months before her release, Katerina was retried for “treason against the state” and sentenced to eight years and three months in a medium-security penal colony.

Former Belteleradiocompany journalist Ksenia Lutskina, who was suffering from worsening cancer in custody, was sentenced to eight years in a low-security prison.

The verdict in the “BelaPAN case” has been delivered. Andrei Aliaksandrau was sentenced to 14 years in a medium-security penal colony, Iryna Zlobina to 9 years in a low-security prison, former news agency director Dzmitry Navazhylau to 6 years in a medium-security penal colony, and BelaPAN editor-in-chief and director Iryna Leushina to 4 years in a low-security prison.

Andrei Aliaksandrau, Iryna Leushina, and Dzmitry Navazhylau were accused of founding and leading an extremist group. Aliaksandrau and Navazhylau were also charged with tax evasion. All were recognised as political prisoners.

Nasha Niva media managers Andrei Skurko and Yahor Martsinovich were put on trial. They were accused of paying utility bills as individuals, not as legal entities. Despite paying compensation and withdrawing the case, they were sentenced to two and a half years in a low-security prison.

The media continued to assign the status of “extremist groups and organizations”. Apart from “extremists”, “terrorists” also appear in the media. For instance, TUT.BY journalists Volha Loika, Alena Taukachova, editor-in-chief Maryna Zolatava and CEO Liudmila Chekina were declared “persons involved in terrorist activities” by the KGB during the investigation of their criminal case.

Criminalisation of media consumption. The heroes of the independent media materials are in danger. Military analyst Yahor Lebiadok was sentenced to five years in a medium-security prison after having commented in one of the “extremist” media. The wife of political prisoner Ihar Losik, Darya Losik, was arrested after giving an interview to the Belsat TV channel and sentenced to two years in a low-security prison in 2023.

Screenshot from an interview with Darya Losik on the Belsat TV channel

Audiences take risks by sending content to independent media. After Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, readers send the media photos and other information about the movement of Russian troops on Belarusian territory. Some of them have been prosecuted for “promoting extremist activities”. They are still being punished for reposting, commenting, subscribing and liking.

Newsrooms are now thinking not only about their security, but also about the security of their audiences. They are finding technological solutions to enable their readers to safely share and consume information (using chatbots, introducing anonymous comments). But the very fact that readers continue to send information to independent media and share their opinions indicates a high level of trust from their audiences.

Internet censorship is in place. In 2022, the state fully or partially restricted access to more than 3,000 Internet resources — independent media sites, Telegram channels, and chat rooms.

Access to the content of Internet resources has been simplified for special services. According to Lukashenka’s decree, telecommunications service providers and owners of Internet resources have three months to register in a special information system for electronic interaction with special services and prepare their resources for unhindered online access by security services.

In 2022, Russian authorities began blocking Russian users’ access to Belarusian independent media due to their coverage of the military conflict in Ukraine.

Criminal prosecutions were getting tougher. Since January 2021, criminal cases against journalists have increased exponentially. Media workers were suspected of “providing financial support to protests”, “evading taxes” and “insulting the President of the Republic of Belarus.”

Criminal sentences for journalists have begun to be handed down. For instance, on February 18, 2021, Belsat journalists Katerina Andreeva and Darya Chultsova were each sentenced to two years in low-security prison for live-streaming a protest rally in memory of killed Minsk citizen Raman Bandarenka. [In November 2020, Bandarenka was beaten to death in the Square of Change, one of the most famous protest sites in Minsk.]

Belsat journalists Darya Chultsova (left) and Katerina Andreeva (right) embrace before the first court session. Photo: TUT.BY

In September 2022, Darya was released and left Belarus. Katerina faced another criminal trial and was sentenced to eight years and three months in prison.

The longest sentence — 15 years in a colony of the enhanced regime — was handed down to Ihar Losik, a media consultant and blogger.

Raids, searches and arrests of newsrooms. On May 18, 2021, the independent media in Belarus faced “black days”. On that day, the authorities attacked TUT.BY: they carried out searches, confiscated equipment, blocked accounts, and completely shut down the Internet resource. Fifteen people were immediately detained. Criminal charges have been filed.

On July 8, 2021, Nasha Niva‘s editorial office and staff homes were raided by law enforcement officials. Four people were detained. The equipment was seized. Criminal cases have been brought against the managers of the media, Andrei Skurko and Yahor Martsinovich.

Editorial office of Nasha Niva after the search. Photo: Nasha Niva.

On July 16, 2021, raids were carried out in seven towns across the country, targeting 17 journalists working with RFE/RL and Belsat. Six people were subsequently detained.

On August 18, 2021, the staff of BelaPAN, the only non-state news agency in the country, were searched. The searches and seizure of documents were part of the criminal case against the agency’s former deputy director, journalist Andrei Aliaksandrau. He was charged in January of the same year with “organising or participating in activities that seriously undermine public order”. Criminal cases have been filed against BelaPAN editor-in-chief and director Iryna Leushina and ex-director Dzmitry Navazhylau.

In 2021, 146 searches of journalists’ homes and editorial offices were recorded.

Repression against non-state journalists and media outlets has been systematic and aimed at virtually destroying the independent media sector in the country. Belarusian media professionals have been outlawed and forced to move abroad on a massive scale.

Newsrooms have started to leave Belarus. Attacks on independent media led to emergency relocations to Ukraine, Georgia, Poland, Lithuania, and other countries.

The process of relocation is still ongoing. Despite the fact that the media are working in exile, they continue to retain their audience and work for Belarusians.

The publications and the media themselves are increasingly being recognised as “extremist”. The media continue to be stripped of their media status. Instead, they are given another status — that of an extremist group. This allows law enforcement agencies to arrest media workers and charge them with “participation in an extremist group”.

Criminalisation of media consumption. There are additional risks for audiences of “extremist” media. Liking, subscribing, commenting, reposting, and sharing information with the editorial team can result in both administrative and criminal charges.

Commenting on high-profile cases online becomes dangerous for Belarusians. For example, in the “Zeltser Case”*, at least 124 people have been detained for comments, reposts, leaks of data from security officials, and publications on social networks. By 2023, 99 people had been sentenced to prison. This is one of the most serious cases in Belarus, according to human rights activists.

* In the year 2021, two people, the KGB officer Dmitry Fedosyuk and the IT specialist Andrei Zeltser, were killed in a shoot-out in an apartment in Minsk. There was a wave of detentions of those who spoke out on social networks and condemned the law enforcement officers.

The pressure on the print media continued. Many newspapers were excluded from the state-monopolised print distribution system and denied the possibility of printing in the country. For instance, the printing house refused to print Brestskaya Gazeta. The weekly Novy Chas disappeared from the kiosks of the state monopoly Belsayuzdruk. The State House of Press unilaterally terminated its contract with the regional non-state newspaper Intex-press (Baranavichy), and Belposhta removed the newspaper from the subscription catalogue. The Regional Gazeta (Maladechna) and Inform-progulka (Luninets) were forced to cease publication of their print versions.

Novy Chas employees pack envelopes with the latest issues of the newspaper for their subscribers. Photo: Novy Chas

The pressure continues in 2022-2023. There are no print versions of the independent media to find out what is happening in the country. Some newsrooms have relocated, some have gone online, some have closed, and some have refused to cover socio-political issues.

Detentions, searches, and seizures of equipment. The journalists were detained while working in the streets, supposedly for their ID checks, and taken to the district police department, cutting them off from the events and preventing their audience from being able to get information on the spot. Their equipment and information carriers were seized and destroyed. Reporters and photographers were physically removed from the streets and detained both during the broadcasts and before the rallies.

Law enforcers began searching the offices of independent media outlets and the homes of journalists and media managers. As a rule, the search ends with detentions and seizure of equipment.

Physical violence and injuries. Although journalists were not protesters and wore special vests, they were among those detained and brutally beaten. From August 9, 2020, to the end of 2020, there were at least 62 cases of physical violence against journalists.

Natalia Lubnevskaya, a journalist wounded by a rubber bullet, is being accompanied by her colleagues. Photo: Uladz Grydzin

Three cases of injuries were also registered. On August 10, 2020, Nasha Niva journalist Natalia Lubnevskaya was shot in the leg with a rubber bullet while she was covering a protest rally in Minsk. The video published by Nasha Niva clearly shows the journalist being shot at close range by a man in uniform.

Administrative courts. First, there were administrative cases. Journalists were sentenced to 10-15 days in prison for “participating in the rally”. Then the charge of “disobeying an official” was added, which allowed for 30-day administrative detention.

With identical verdicts and witnesses wearing balaclavas and using false names, so-called “conveyor trials” were held. The judges did not allow the lawyers to defend their defendants, question anonymous witnesses, and establish their identities. The decision to hold court hearings in an online format was explained by the epidemiological situation. At the time, the authorities were actively denying that there was a COVID epidemic in the country.

A journalist who covered the rally (left) and an anonymous witness in a balaclava (right) can be seen on a laptop screen on the judge’s table before the start of the trial held via Skype. Photo: TUT.BY

Start of the criminal prosecution. Journalists become the subjects of criminal cases. In 2020, six of them were charged with “organising and preparing activities that grossly violate public order” for their coverage of protests, “disclosing medical secrets” after a high-profile story was published, and “defaming” an official.

On December 22, 2020, part of the Press Club Belarus team also fell under “criminal case pressure”. Founder Yuliya Slutskaya, financial director Sergey Olshevski, program director Alla Sharko, and cameraman Peter Slutsky were kept in a pre-trial detention facility for eight months, accused of tax evasion. They were recognised as political prisoners. The criminal case was closed in 2021. At the same time, Press Club Belarus was liquidated in the country, along with hundreds of other Belarusian NGOs.

Persecution of journalists who quit the state media after the events of August 2020. The hunt was on for workers who spoke out publicly against violence and lawlessness, took part in protests or simply quit their jobs. For example, in September 2020, state television anchors Denis Dudinsky and Dzmitry Kakhno were each sentenced to 10 days of administrative arrest for participation in a rally.

In December 2020, former Belarusian TV and Radio Company journalist Kseniya Lutskina was detained in the “Press Club case” for allegedly failing to pay taxes to an organisation she did not even work for. She spent two years in the pre-trial detention facility and was eventually sentenced to eight years in a low-security prison, but this time on another charge: “conspiracy or other actions committed with the purpose of seizing state power”.

The criminal prosecution of journalists who quit their government-run media outlets — as an act of revenge against recently loyal “voices” of the authorities — will continue in the future. Thus, in 2023, a former correspondent and presenter of the state television, Dmitry Semchenko, who had resigned in August 2020, was sentenced to three years in a low-security prison for “incitement to hatred”. This is how the court interpreted Semchenko’s three posts on VKontakte [one of the most popular social networks in Belarus and Russia] and Instagram.

Blocking of websites. As many as ninety-two independent media and political websites were blocked by the Belarusian Security Council on the grounds of “harming national interests”. The decision was taken on 21 August 2020. However, all resources have been inaccessible since 9 August 2020. The justification for the measures was that the blocked outlets were “negatively portraying the situation in Belarus after the end of the election campaign and discrediting the work of state bodies”. The blocking of the independent media is set to continue in the future.

News photographers filming the protest rally. Photo: Pavel Krichko

Prohibition to print and distribute printed media. The authorities do not allow newspapers, which give an unbiased account of what is happening in the country and are a familiar form of dissemination for older people, to be printed and delivered into the hands of their readers. Following the August 2020 elections, four national newspapers — Narodnaya Volia, Komsomolskaya Pravda in Belarus, Svobodnye Novosti Plus, and BelGazeta — were banned from printing and distributing. The reason given by the State Press Committee was “a broken printing press”. At the same time, the state-owned newspapers were printed during the days of the above-mentioned breakdown.

Deprivation of mass media status. The Belarusian legislation provides for a specific form of sanctions against the media: written warnings that are issued by the Ministry of Information. If a media outlet receives two or more warnings within a year, it can be closed by court order.

A solidarity action by journalists near the district police station in Minsk where their colleagues are being held. Posters reading “I’m not protesting, I’m working”, “I’m on duty” and “Freedom for journalists”. Photo: TUT.BY.

For example, the country’s largest news portal, TUT.BY, received four warnings in August and September 2020. The Ministry of Information filed a lawsuit in court to suspend the online edition of TUT.BY. The mass media status was suspended and in December 2020, the Economic Court revoked the media status of TUT.BY. However, as an Internet resource that is legally allowed to collect and disseminate information, the media continued to function.

In 2021, the authorities physically destroyed TUT.BY, but the editorial board managed to escape, retain part of the team and continue working for its audience already under the name Zerkalo.

In 2020, the independent Belarusian media sector played a significant role in the democratic movement, and in 2021, it was the target of an unprecedented purge by the authorities.

Terms and conditions

Partial or full reprint is permitted subject to following terms of use.

An active direct hyperlink to the original publication is required. The link must be placed in the header of the reprinted material, in the lead or the first paragraph.

Reprints, whether in full or in part, must not make changes to the text, titles, or copyrighted photographs.

When reprinting materials from this page, attribution must be given to the Press Club Belarus “Press under Pressure” project, collecting evidence of repression against independent media and journalists in Belarus.