The case started on 25 March 2020 when a search was conducted at Siarhei’s home and the editorial office, and Siarhei was subsequently detained. Yet already on April 4, 2020, the General Prosecutor of Belarus revoked the imprisonment resolution. The journalist was freed until 8 December 2021 subject to an undertaking not to leave the country.

Siarhei Satsuk was recognized as a political prisoner. Belarusian Association of Journalists managed to discover that in addition to bribery, Satsuk is being accused of inciting hatred and of abuse of power. However, no further details were available.

On October 26, 2022, the Minsk city court brought the editor-in-chief of Ezhednevnik a verdict of guilty under three articles of the Criminal Code of Belarus: ‘inciting hatred’, ‘abuse of power’, and ‘bribery’. The journalist was sentenced to 8 years of general regime colony and also a fine of 500 base values (16,000 BYN, or about 6,300 USD). Besides, the court decided to exact from the political prisoner 12,384 BYN (about 4,770 USD).

On March 17, 2023, the Ministry of Internal Affairs added Satsuk to the list of persons involved in extremist activities.

Siarhei Satsuk’s story is told by his brother and colleagues.

Siarhei and I are twins. And it’s true what they say about twins. I can feel what he feels and I trust him as I trust myself. We are very close.

As a child Siarhei had no plans of becoming a journalist. We both worked at a construction site after retiring from the army. Siarhei was an excavator driver. It was the early 1990s, hard times, no money.

We both loved making up stories. Siarhei started to write fantasy novels while working at the construction site. He showed his drafts to an editor once and two of his books were published! So he decided to work with texts and become a journalist. When he was 23, Siarhei enrolled at the Faculty of Journalism and started to work at Belaruskaya Delovaya Gazeta (BDG). And he took me with him. I worked at the police at that time, Security Department, but it was clear for me that the authorities and I have our separate ways.

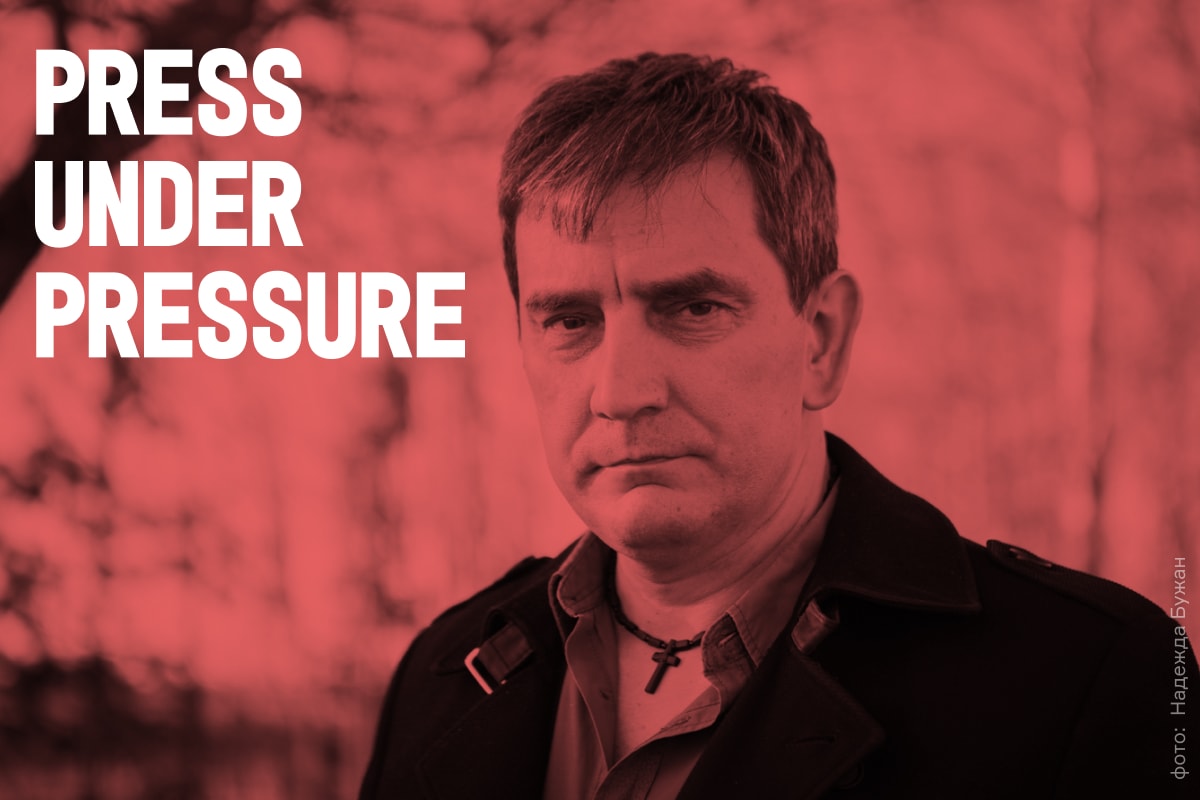

Siarhei Satsuk. Photo: Nadzeja Buzhan

BDG was closed by the authorities later. I left it to work as a legal adviser and Siarhei stayed in journalism. Thus, his colleagues and he came up with the idea to establish Ezhednevnik. It was in digital format at first, an emailed out PDF newspaper. Siarhei’s team included Yuri Zisser back then.

Why investigative journalism? Back at Belaruskaya Delovaya Gazeta, Siarhei was a member of the legal and incidents department where people came telling their stories, complaining about injustice. Siarhei had to deal with investigations and he began to like it with time. More and more people came to him. He once said he had enough stories for investigations for 10 years ahead!

Some investigations were not like all others. For example, when a death squad investigation was published we went to meetings in two cars and looked out for surveillance. In fact, Siarhei often received threats due to his investigations. He once found a funeral wreath at his door.

Siarhei knew they could come to him; he was even openly warned. He was scared, for himself, for his family. But he stayed when they opened a case against him. He was under the undertaking not to leave the country and he hoped everything would end naturally since there was no hard evidence. He thought they wouldn’t go for it. Yet it turned out the authorities are so afraid of any alternative information that they try to pin down any source of it.

I write letters to Siarhei but have received no response from him so far. Siarhei’s wife sends me news about him from time to time. He’s in a fighting spirit. He is making notes, he says he’s collected stories enough for several books. He’s staying optimistic!

I met the Satsuk brothers in 2001 when I started to work with Belaruskaya Delovaya Gazeta. It was the largest and the most authoritative private edition in Belarus at the time. Even the governmental officers, top officials read the newspaper and responded to articles.

I know the Satsuks are very thorough fact-checkers. They are very much alike in general, people often confuse them. They were in charge of criminal acts and investigations at the office. People used to come to the editorial office seeking justice. A visitor could have spent huge money on lawyers and courts but achieved nothing and then came to the editorial office begging for a journalist’s help. The Satsuks usually helped such people, often arguing with the officials. Some people, who thought they’re the smartest, tried to use the journalists to their benefit and ordered articles to throw mud at their competitors. But the Satsuks never did that.

Investigations are money consuming. While one can write a dozen of news during one press conference, investigations take weeks of hard work for just one material: meetings, correspondence with governmental institutions, traveling.

Siarhei Satsuk. Photo: Nasha Niva

In Belarus, unfortunately, leaks from the governmental offices, literary reworked, are often called investigations. The Satsuks worked in a different way. Publishing unverified information in an investigation can seriously affect both the editorial office and the heroes of the article damaging their reputation. After the authorities bankrupted BDG with fines, Siarhei Satsuk established Ezhednevnik where he tried to conduct actual investigations.

Investigations are a dangerous field, too. Especially when the published materials concerning people in power. That was what happened to Siarhei when he touched healthcare business in a famous investigation about overpriced medical equipment procurement.

They tried to accuse him of lies at first. It didn’t work. Then, bribery. Judging by the duration of this investigation I can assume they can’t prove the fact of taking a bribe. Siarhei knew very well that any bribe would destroy his reputation as a journalist. And the level of his life shows no evidence of receiving bribes. Prior to his imprisonment, Siarhei had hard times financially and was selling his almost finished house.

I’m not in contact with him now because letters in prison are censored and I’m not willing to supply information to the government. Willing to help, I suggested I’d be Siarhei’s bailsman so that he would be released from the detention centre for the duration of the investigation. But they didn’t release him.

Prior to his latest detainment, I advised Siarhei to flee from Belarus and on the ways to do it. But he refused to and didn’t want to leave his family.

I met Siarhei at Belaruskaya Delovaya Gazeta. Different people gathered there: several historians, a philologist specializing in Bunin, a former KGB lieutenant colonel… Siarhei, who came to the investigation department, stood out even among those: prior to the best newspaper in Belarus, he worked as an excavator driver and wrote several fantasy novels published by a famous Moscow publishing house. After that, he set a goal for himself to become a journalist and studied at the Faculty of Journalism simultaneously. He became one of the few certified journalists at BDG.

Siarhei Satsuk. Photo: Euroradio.fm

Siarhei is goal-oriented. Stubborn even, in topics he worked on before. He is also thorough in working with his sources, and he’s brave: he conducts very risky investigations and makes conclusions, forms an opinion.

Siarhei is one of the few people in journalism who are really passionate about it. Many of my colleagues had and still have interests outside journalism, but for Siarhei, it is both a job and a hobby.

The most striking story and at the same time one of the most serious investigations he has ever done is the story of corruption at Belarusian State Circus. He worked on it in the late 1990s when people started to disappear in Belarus and Russia. Not everything he discovered was printed at the time. But it was enough for Siarhei to get detained for the first yet not the last time, as we know now.

Terms and conditions

Partial or full reprint is permitted subject to following terms of use.

An active direct hyperlink to the original publication is required. The link must be placed in the header of the reprinted material, in the lead or the first paragraph.

Reprints, whether in full or in part, must not make changes to the text, titles, or copyrighted photographs.

When reprinting materials from this page, attribution must be given to the Press Club Belarus “Press under Pressure” project, collecting evidence of repression against independent media and journalists in Belarus.