Just over a year after her arrest, Volha was additionally charged with “insulting a public officer on the Internet”. Judge Maria Aliferuk sentenced her to one and a half years of home confinement. Ultimately, the cumulative sentence amounted to two and a half years in prison.

Released, Volha Klaskouskaya went to Switzerland, where she now lives, works and recuperates. She spoke to the Press under Pressure project about her experiences in prison, the information blackout behind bars and her return to journalism..

I was aware that I would eventually be imprisoned because I had participated in numerous protest actions, painted graffiti, and left comments online without concealing my identity. When the officers from the Main Directorate of Combating Organised Crime and Corruption detained me, I immediately realised it would be a long process.

It was about a spontaneous action in October 2020. The Serabranka community in Minsk was really active during the protests. They put up a strong resistance to the police. I kept an eye on what was going on in the neighbourhood chat and took part in the actions myself. The participants of that action did not know each other. We blocked traffic in Serabranka with our bodies. The day before, other people did the same thing and managed to stop a lot of police wagons: they got stuck at intersections. Of course, we let ambulances pass. There were a few instances when the drivers asked us to let them through because they had a small child in the car.

An ambulance arrived, and we told the medics to drive by and that we would do everything so that they could drive safely. They replied that they were not on an urgent call, and since everyone was stuck, they were willing to wait with the rest. And they added: “Long live Belarus”.

After the last protest action, I was heading home and made a mistake. As an experienced rebel, I knew it wasn’t a good idea to go back through the courtyards on my own. But that day I broke the rule.

I ran out of cigarettes and bumped into a guy who was smoking, so I asked him for a cigarette. He wasn’t involved in the action. He was just returning from his girlfriend’s place. We were attacked by plainclothes police. The guy was badly beaten. I shouted that he had nothing to do with the action. He was completely random. It certainly didn’t help. Then we were transferred from one van to another, and we were badly beaten. At the police station, the boy was still being beaten, but I was left alone.

Later on, Anton Sakovich, one of the operatives, summoned me and threatened to shoot me. He showed me a gun and told me to stand against the wall. I felt pretty bad. I was dizzy and nauseous, so I asked them to call an ambulance. Suddenly people with cameras burst into the room, wanting to make a “repentant” video. They lashed out at me, like “How did you fall so far as to start blocking roads?” I also snapped at them and called them criminals. I didn’t say what they wanted me to say. The propagandists censored my slurs. Political prisoners who were arrested later and saw the video told me that I was rather silent in it.

I don’t see myself as a heroine, it was all just a turn of events. I am just lucky.

These are not “repentant” videos, and I think that everyone understands it. It’s wrong to condemn someone for incriminating themselves while in captivity and under torture. There are just a bunch of edited clips. It’s a pretty scary and tragic situation for anyone who falls into the hands of the punishers.

Both the operative and those filming me were very angry that they did not get what they wanted. The operative started to threaten, saying, “Oh, you’re silent now? No worries, when you start wetting yourself, you’ll start talking”.

After a while, they called an ambulance and it took me to the clinic. The doctors there diagnosed a concussion and a closed head injury. I was left in the hospital, chained to the bed and accompanied by an escort. Normally, in a situation like this, a person is kept in a separate ward. However, there was no such option available, so I was sharing the room with another patient. Her relatives came to visit and when they offered to treat me to fruit, the police shouted, “She’s under suspicion of a crime! You can’t give her anything!”.

Then the investigator came to the hospital and told me that I’d been detained under Article 342. She asked if I was going to make a statement, and I said I had nothing to discuss with her.

I was in the hospital for a day until some masked men broke into the ward and kidnapped me. My ward mate started to cry and shout, “Volechka, they’ll kill you! Where are they taking you?”. The medics came running and started negotiating with these unknown men in masks on my behalf.

The doctor said that I needed to stay in the hospital for further observation. But I was still taken away from there. By the way, the clinical report states that the patient was removed from the department by police officers and unknown masked men without the consent of the doctors on duty [The editorial team was provided with a copy of the report – Ed. note].

Just to let you know, they grabbed me so fast that they didn’t even let the medics remove the catheter from my hand. I was still wearing it when I was taken to the temporary detention centre. It took a few days for them to remove it. It had started to get infected.

They didn’t offer any medical assistance. They just told me to sign in some register and confirm that I wasn’t complaining about my health. I replied that I had a lot of complaints.

And said that they had no right to process me at all because I was supposed to be in the hospital. The answer was: “Whatever”. I was supposed to be sent to the Zhodzina pre-trial detention centre pretty quickly, but they wouldn’t admit me because of the injury. They did not want to take responsibility. After that, I was sent back to the TDF, but after a while, I was still taken to Zhodzina.

What helped me was that I had a sense of moral superiority over the investigators, the escorts and all the other system personnel. I looked down on them, they were like servants to me. I always knew that the truth would prevail in the end, and that those in positions of authority over me were ultimately insignificant figures.

During my sentence, I passed through five pre-trial detention centres. When I started, I was thrown in at the deep end and put straight into what you might call the “pressure cell”. I was in the basement cell alone. It was pretty humid in there, and there were puddles on the floor. They didn’t take me out to the shower or for exercise. For a while, no one even entered the cell – the guards just watched through the peephole.

One day, a guard came by and I just knew we could have a chat. I asked: “What does it all mean? This is not a punishment cell. Why such complete isolation?” He said I was brought by a special escort that told them I had COVID-19. But I wasn’t infected, they just made it up.

The cold and humidity really took their toll on me, and I ended up falling ill and developing uterine bleeding, which continued throughout my time behind bars.

Before long, a woman who had been arrested for the third murder was brought into my cell. He had been labelled “repeat violent offender”. My Article 342 is a misdemeanour, so I was not supposed to share a cell with those accused of felonies.

It was obvious that this woman was brought in to put pressure on me psychologically. She told me about her murders and laughed. She said her only regret was that she was arrested and didn’t get to finish the vodka. I felt uneasy. At night, I often had this feeling that once I fell asleep, she would suffocate me with a pillow. It became an obsessive thought that haunted me.

After about 10 to 15 days, I was transferred to an ordinary cell, but there was no place for me as all the bunks were already occupied. I asked the guard where I should sleep, and he said I could take the bench.

The first political prisoner I met there was Masha Babovich. She was arrested for making the graffiti “We will not forget” next to the memorial at the place where Aliaksandr Taraikouski was killed. Also, there was Natasha Rayentava, who was accused of biting a police officer. Some other people were arrested for domestic crimes, and they were really nice to us. We were all friends, supporting each other, telling different stories, playing prison games and joking around a lot.

In Minsk pre-trial detention centre, I shared a cell with Viktoria Kulsha. We joined forces to fight the administration, went on hunger strikes and so on. Natallia Hersche was in the cell across the hall. As luck would have it, the feeders were opened at the same time, and we even got to chat. One day, Natallia showed us a poster saying “We announced a hunger strike, three people, over correspondence ban”. Viktoria and I decided to join. We kept in touch and gave each other a hand when we could.

The prison guards at the pre-trial detention centre and the correctional facility knew I was a journalist. They also knew about the case and my background. I wouldn’t say they were exceptionally hostile towards me. But they were pretty cheeky, asking things like, “Did the Polish puppeteers pay well?” or “Is it worth lying for Polish money?” or “Will you do an article on us after your release from prison? Just don’t lie!”

My journalistic experience behind bars helped a lot. As a creative professional, I memorised details and trifles. From the moment I was arrested, I knew I’d be writing about it. I even memorised the names of most of the guards and made sure they introduced themselves. Then I wrote about everything in my “prison diaries”. I revealed the identities of the guards, documented their crimes, and described the painful experiences of political prisoners who asked me to do that.

Longing for information in prison is pretty tough. The deprivation is a torture that causes great suffering. You’re feeling a bit disoriented, and the prison guards, in the face of this information hunger, have created a lot of myths and spread them. If you don’t have another source, you have no way of verifying the information. At some point, you start to wonder: “Could this be true?”

The lack of information was unsettling me throughout the trial. We only had a few bits of information there.

When you’re on calls with family, there’s an operative sitting next to you. If it’s a video call, you don’t say anything at all, because political prisoners had to talk without headphones.

Volha video calling from prison

Once, during a video call, when Dad said the situation was bleak, the operative responded immediately: “Ms Klaskouskaya, you should only discuss the weather. Is this clear? Otherwise, I’ll stop the video call right now”.

At first, independent publications were still distributed in the remand centres – the newspapers Novy Chas and Belorusy i Rynok. The letter flow was great at first – it seemed like they were delivering them all to us. We also received letters from other countries, including the Netherlands, Canada, Poland and Germany. Then, gradually, they started to cut back. By February 2022, almost all letters were censored. We only received scarce letters from close relatives.

Sometimes they staged things in the facility. They pretended they weren’t stealing our letters, but that some letters just didn’t make it past the censors. It was a masquerade for various inspections. Everything was clear as day for both the administration and inspectors, but they still wanted to prove during the inspections that our letters weren’t just stolen, but that they contained something unacceptable and didn’t pass censorship.

I was summoned one day and told that they had to destroy a letter I had received because it was written “in a cynical manner”. It turned out that the letter was from Natallia Hersche. Her first letter got through, but that one wasn’t given to me. I laughed and asked what was cynical about Natallia’s letter. Did she describe how good life in Switzerland is and how bad it is in Belarus?

I was released in December 2022 and fled to Switzerland in February 2023. Naturally, I could not return to work in Belarus. The police came to see me as soon as I was released and told me not to “stick out”, otherwise I would go back “to where I came from”. Even without them, I knew it was risky to write texts, give interviews or make any public comments in general.

I did give one interview to the Viasna Human Rights Centre, though. I was feeling pretty weighed down mentally. There were so many testimonies, so many factual details, and let’s not forget the inmates who asked to share all this. Being forced to keep my mouth shut was very painful.

That interview was published anonymously, but if you wanted to, you could work out that it was me. By analysing style, details, different circumstances… But when I gave that interview, I felt such a relief! Although I did expect them to come back for me.

Six weeks after I moved to Switzerland, I started to become more open and public. I started giving interviews to fellow journalists and talking about my experiences. I also started writing again, going back to journalism.

My first text was called “Belarusian football gets a red card because of the regime’s contrariness”. A protest to prevent Belarusian footballers from taking part in major international competitions was held near UEFA headquarters. I didn’t have a computer yet, so I wrote the text on my phone. I was really worried about how things would turn out and whether I’d lost my way.

In general, I have been very careful about which newsroom I want to work with. I have a lot of respect for all Belarusian editorial teams, but Novy Chas is something special for me. I have a great affection for it. This is a publication that political prisoners could receive in prison back in the day. It’s also in Belarusian.

I don’t mind if newsrooms work in Russian, but it’s easier for me to express my thoughts and write in Belarusian. I knew the people who worked there pretty well. In a nutshell, everything came together and I decided I wanted to work there. And I never regretted it. We have such a wonderful team!

It still happens that I get overwhelmed with emotion sometimes. I’m still recovering because a person who comes out of prison is affected both physically and mentally.

I often find myself sitting at my computer, looking at an empty screen, even though I really want to write something. I have all the information I need, but I just can’t seem to get started. I just say to the editors: “Friends, forgive me, I will not be able to write an article in the next few days”. And I get so much understanding! No one scolds you or rushes you, on the contrary – they encourage me to look after myself. That kind of attitude speeds up my mental recovery.

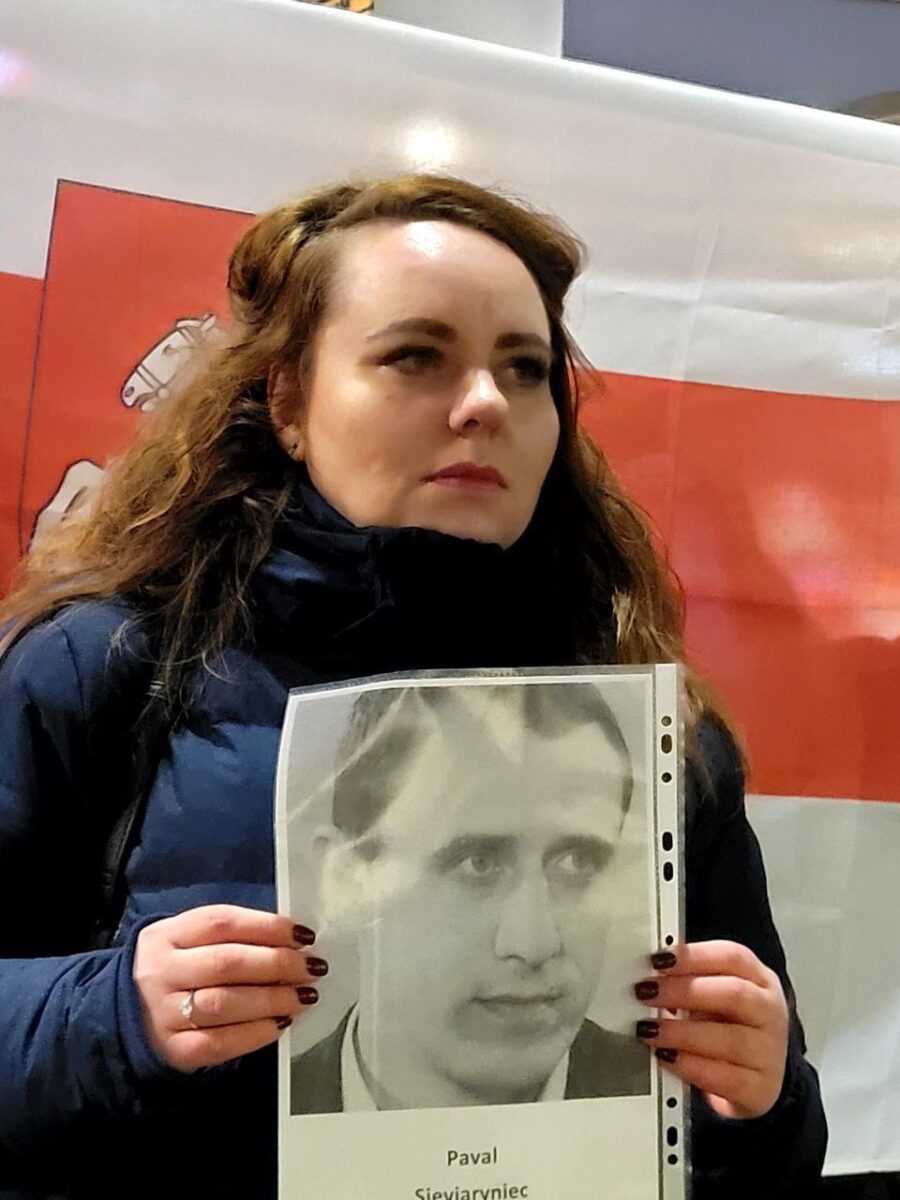

Volha Klaskouskaya and Natallia Hersche

I also do occasional writing for the BAJ and the Swiss. This is also a journalistic work, but it is not published. These are slightly different things. I work with Swiss human rights defenders, politicians and various organisations.

I started from scratch here and now I have a great network of contacts, I’ve published more than 20 parts of my “prison diary”, I’ve received the Aliakhnovich Prize, I run my Telegram channel and I’m waiting for the publication of “prison diaries” in the form of a book. Once I’m fully recovered, I’ll be able to do even more. I am already feeling a great sense of fulfilment and satisfaction from my work.

Terms and conditions

Partial or full reprint is permitted subject to following terms of use.

An active direct hyperlink to the original publication is required. The link must be placed in the header of the reprinted material, in the lead or the first paragraph.

Reprints, whether in full or in part, must not make changes to the text, titles, or copyrighted photographs.

When reprinting materials from this page, attribution must be given to the Press Club Belarus “Press under Pressure” project, collecting evidence of repression against independent media and journalists in Belarus.